- Home

- Joanne Drayton

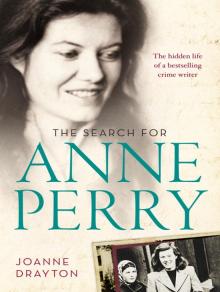

The Search for Anne Perry

The Search for Anne Perry Read online

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Every effort has been made to identify the photographers of images contained in personal collections. If a photographer has not been identified, please contact the publisher with details, and acknowledgement will be made in any reprint or future edition of this work.

DEDICATION

For Suzanne Vincent Marshall

&

thank you to my mother

Patricia Drayton, an old girl of CGHS,

whose special interest in this story helped to make it happen

&

Meg Davis and Kate Stone,

whose generosity and intelligence

have been unfailing.

The rest is for and about Anne Perry.

CONTENTS

Cover

Author’s note

Dedication

Prelude

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Picture Section

Postscript

Endnotes

Select Bibliography

Searchable Terms

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

PRELUDE

Meg hurried back from lunch. It was Thursday afternoon and the next day was her last in the office for two weeks. The weather was warming, and she and her partner, Pim, were going to Wales for their summer holiday. The lunch break had been a chance for them to quickly buy some lamps for their new home together. The day was hot and the streets fumy and noisy, with the hum of London traffic intermittently punctured by screeching sirens. The MBA Literary Agents Ltd office, on the corner of Fitzroy and Warren streets, was in a skinny, grey-brick building with white facings, a brown door with a large brass door handle, and a solid black iron railing. Butted against it on one side was a garish little coffee shop, and above the brown door long, thin windows were stacked in pairs; in all, it was three storeys high with a tiny flat on top.

The office was open-plan, so coming through the door was to become immersed in the clack of keyboards, the screech and whirr of the fax machine, the ringing of telephones, and the relentless buzz of other people’s conversations.

As Meg sat down at her desk, Sophie Gorell Barnes told her that a journalist from New Zealand had rung and would call back. Although this was odd — agents usually chased journalists — Meg gave it little more thought.

Two hours later, her telephone rang again. The woman on the end introduced herself as Lin Ferguson. Surprised to learn that Meg knew nothing about the Parker–Hulme case, she proceeded to tell her about two teenage girls, Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme, who had murdered the former girl’s mother in Christchurch in 1954. Then she said breathlessly, ‘And, I think Juliet Hulme is your client, Anne Perry.’

Meg exploded with laughter. It was too ridiculous for words. How could Juliet Hulme possibly be her author of 20 bestselling books, the matronly, ‘matching bag and shoes’ 55-year-old Anne Perry? Finally she recovered enough to say, ‘Come off it — I think you’ve got the wrong woman.’

‘Yeah. I guess I must have. Never mind,’ came a crestfallen voice from the other end, and the line went dead.

Meg recounted the conversation to everyone else in the office, and they all had a ‘fantastic laugh about the whole thing’.

‘It’s incredible,’ Meg gasped.

‘Yeah,’ agreed Sophie, laughing. ‘If you had really committed murder … you’d become Jane Asher and be, like, “queen of cakes”. You’d become Delia Smith and be the “doyenne of cuisine”. You wouldn’t go and write grisly Victorian murder mysteries.’ The next morning, 29 July 1994, the telephone rang again and it was Lin Ferguson.

‘Actually,’ she said, ‘I think it is Anne, and we’re going to publish the story in the Sunday papers.’

‘Well, you think you’re going to, but you’re going to have an injunction in five minutes, so just stay by the phone.’ A furious Meg decided to ring Anne immediately, then their lawyer.

‘Look, I’m really sorry to bother you,’ she began her telephone call to Anne. ‘You know how I have to ask you if we’re going to involve a lawyer? I think we’re going to need to do that.’ She quickly outlined the ‘ridiculous story’ that Lin Ferguson had told her. ‘Can you believe it? There’s a film being made about this murder, and some people have got hold of this crazy idea that it’s you … But we’re going to get an injunction.’

Meg’s words hit Anne Perry like the first wave of an atomic explosion. She felt physically sick. It had happened at last, the one thing in the world she feared the most. For a while she was almost senseless, listening but not hearing, the room receding and her head pounding like a drum. ‘I’m sorry, but you can’t … You can’t refute it — because it’s true.’

There was a sharp intake of breath at the other end of the line. ‘I’m going to phone you back from a more private phone. I’m going to call you back in ten minutes.’

Ruth Needham, glancing up from her desk and noticing the expression on Meg’s face, shot off to Diana Tyler’s cupboard, poured a large Scotch and brought it back for her. Meg emptied the glass, steadied her nerves, then climbed the narrow staircase to the hush of MBA’s attic flat to ring Anne at her home in Portmahomack, in the Highlands of north-eastern Scotland.

‘OK, I still love you. Now, you have to tell me about this.’ And so for the first time they had a proper conversation about Anne’s past, and things began to fall into place. The gaps in Anne’s life that Meg had wondered about, the late teenage years that evaporated in sickness, the furtive glossing-over of certain matters, the way Anne had always made questions disappear as if by sleight of hand — all this Meg had put down to Anne being Anne, but now she realized that it meant a whole lot more. Collecting herself, she began to strategize.

‘What we need is a lawyer to manage the press for us. This is going to be big and we need expert advice.’ She told Anne to sit tight and talk only to her mother and her closest friend, Meg MacDonald. As soon as she got off the telephone, Meg rang their lawyer, who immediately gave her the contact details for Lynne Kirwin, a publicity agent who would help limit the media fallout.

Lynne Kirwin recommended a plan that she hoped would contain things and reduce the trauma for Anne. ‘Anne will have to do an interview for the [Daily] Telegraph, [as that’s] the paper in the UK where other journalists get their facts from. We’ll have one interview there telling the whole story, and Anne doesn’t need to talk to anyone else — we’ll just kill it dead right there.’1

In this ‘huge crisis’, should Meg continue with her holiday plans to Wales, or cancel everything and go up to Portmahomack with a ‘shotgun picking off journalists and fielding phone calls’?2 Finally, she decided to trust Lynne’s reassurances and go to Wales. If she had realized what was going to happen, she might well have changed her mind. As it was, Anne rang her every day she was away. Meg and Pim spent their first week at a bed-and-breakfast in an old farmhouse. There was only one public telephone, in the hall, and the good-natured staff would serve Meg’s cooked breakfast there, while she stood with the receiver in one hand and a fork in the other.

Anne was terrified she would lose everything — her friends, her career, her income and her house. Would it be a repeat of the past, with the same vilification? ‘Am I never to be forgiven?’3 She worried about her brother, Jonathan Hulme, and about the impact on his wife and young children. She feared, too, that the ordeal of having the past raked up again would kill her mother, now known as Marion Perry, who was then 82 ye

ars old and in poor health and living a kilometre or so away at Arn Gate Cottage. But when Anne went to tell her mother the news, Marion showed herself to be stronger than anyone could have imagined; she stood by her daughter in steely fashion. There was something cool, self-assured and calculating about Marion. In her day, her coiffed hair, perfect presentation and glamorous looks had hushed party conversation and stopped men mid-stride. Even in old age, something of the coquettish grace and elegance survived. She was clever at reading people, and past humiliation and social disgrace had made her more astute and determined not to give up the life she and her daughter had rebuilt. ‘There’s no place for tears. If there’s any crying, it’s to be done much later,’ she instructed Anne, and sent her back to her semi-restored stone barn ‘to draw up a list of friends and … do battle’.4 Anne, who would not remember much of what she did during this time, sat down and worked out the people she should see in person, and those she must telephone.

Afterwards she had a conversation which remains vivid in her memory, and which she describes as the hardest thing she has ever done. She rang her friend and contemporary Peggy D’Inverno, proprietor of the village post office and general store, and asked her to come to the house. Anne told her that she and another schoolgirl had killed a woman in New Zealand in 1954, and that it would be all over the newspapers in the morning. This was the first time in 40 years that she had told her secret to anyone beyond her most intimate associates.

That evening she went to see the minister of her local Mormon Church in Invergordon and told him everything. She wept uncontrollably. They prayed together, and the minister predicted that she ‘would not lose a single friend’.5 Her faith was a consolation, but the task ahead was daunting. She had got to know people during her five years in the quiet provincial backwater of Portmahomack. How would they feel about her now? If they felt uncomfortable about her living in the village, she resolved to leave.

On 31 July, the story broke in the Sunday News in New Zealand, under the headline: ‘Murder She Wrote! Best-Selling British Author’s Grisly Kiwi Past Revealed’. Anne opened her curtains the morning after to see that ‘her driveway was a sea of journalists from Australia and New Zealand, who had just got on the first plane [to the United Kingdom] and were now pointing with huge telephoto lenses’, and that television crews were wandering over her property.6 Day and night the telephone ran hot with tabloid journalists soliciting her comment. One journalist who woke her swore ‘on the life of his child’ that he would not send the story out until it was approved, all the while faxing the article to his newspaper.

Anne would spend the next three days ringing the people on her list — family, friends and business associates. She would put long-distance calls through to the United States: to her editor, Leona Nevler; her New York book agent, Don Maass; her film and television agent in Hollywood, Ken Sherman; and her publicist, Kim Hovey. She had no idea how any of them would react, and she feared the worst.

CHAPTER ONE

I

To a Londoner, Darsham is unforgivably remote, bypassed even by the area’s main road, the A12. Its redemption is the East Suffolk railway line, which clatters across the county’s infinitely flat stretches of farmland, linking the ports of Ipswich and Lowestoft. The journey from London takes two trains and too long. The connection at Ipswich is intermittent; the antiquated carriages baking under brilliant blue skies in summer, and in winter breathing draughts of freezing air that whip ankles, knees and necks. Darsham Station is a mile from the village. In cold and rain, it is a damp, dreary trip between fallow fields; in the warmth, it is a delight of soft, sweet air and narrow country lanes edged with wild flowers and lush hedgerows.

This is an ancient part of England, with a history so old it stretches back to the margins of memory, where myth and legend merge with fact. Just a little way down the East Suffolk line, near Woodbridge, are the mounds that mark the grave sites of Sutton Hoo. Here, an early medieval Anglo-Saxon king, believed to be Rædwald — the legendary leader of East Anglia who died in about 624 — was buried in a ship that was intended to carry his immortal soul to its rest. Mounds mean something more in Suffolk, and so does the soil that has sustained human habitation for 700,000 years. Who knows what other ancient treasures are buried in the earth around Darsham? Whatever the answer, it has certainly proved a fertile site for the imagination.

The area has also been a rich hunting ground, especially in the eighteenth century, when game graced banquet tables and killing it was an aristocratic sport. There are reminders of the animals of the hunt in the village still. The name Darsham comes from the words ‘Deores Ham’ (home of the deer), and the local pub is The Fox. Of the half-dozen surrounding agricultural properties, White House Farm, with its home dating back to 1750, is probably the most illustrious. It has changed hands just a few times over the centuries. In the village there is a shop, a post office, a school, some tradesmen, a few small businesses (including a pottery and a tile factory), and two ghosts.

This is a modest ghost population for such an old place. One, known as Mandy, dances terrifying country jigs; the other, dubbed the Window Dweller, is believed to be a manifestation of the harrowed soul at Thomas Farriner’s bakery who inadvertently lit the Great Fire of London in 1666. There have been nocturnal sightings of the Window Dweller since the seventeenth century, when its smoky presence was detected against the glorious stained-glass window of All Saints Church.

It was in Darsham, in the far reaches of Suffolk just a few miles from the North Sea coast, that Anne Perry decided to bury herself on her return to England in 1972. It was an escape but also a planting of her imagination in home soil. For nearly five years she had lived in Los Angeles, that glitter city with its lights, billboards, huge buildings and cosmopolitan buzz. Although she had gone there to find herself and realize a dream, it had proved a fruitless search. She had moved from job to job, never settling, never finding her place. Then, almost at the same time as she lost her job, she learned of her stepfather Bill’s precarious health.

When she first went to California in January 1967, it was to take up a position as nanny with a family in Moraga outside Oakland, across the bay from San Francisco.1 She arrived to find them in turmoil. The wife, who had died suddenly, had ‘lain on the linoleum floor of the family room for hours … before they bothered to notice she was dead’.2 The children, three sons aged eight, five and three, were unhappy and obstructive, and Anne felt uncomfortable, alone and physically isolated. ‘We were miles away from any public transport. I was totally islanded in a pretty grim situation.’3 She found her escape with the neighbours, Ray and Chlo Barnes, a couple whose faith in the Mormon Church was unshakeable. They were kind and nurturing when Anne was vulnerable and depressed. For years she had been considering alternative religions, and options within Christianity, but nothing fitted, or filled the gap that, if she focused on it, was an all-consuming abyss. This new faith was simple enough, but it answered everything. ‘Mormons believe we are all children of God, and that the fall from perfection is part of life.’4 Imperfection was not aberrant, emanating from something inherently evil, but everyday and ordinary.

She did, however, stumble over the Mormon version of Creation. Ray Barnes told her to pray about it. ‘He said, “Don’t try to argue about Creation or whatever — ask God.” When I woke up in the morning, the room was full of light.’5 This epiphany was beautiful and reassuring, and the threshold of a new beginning. The Mormon Church gave Anne permission to be normal. It was her true release from prison. She could be a child of God if she were a Latter-Day Saint, so she became one.

But there remained a huge hurdle: she would have to tell the officiating pastor about her past. How would he respond? Would she be rejected? What difference would it make to the way they treated her? She felt stripped bare again, ugly and exposed. What he told her, though, became seared in her brain: her sins could be ‘washed out of the Book of Remembrance in Heaven’. This is how she remembered it much later for Rober

t McCrum: ‘If you have something you [are] ashamed of, you want it washed away, and if you repent, it can be.’6

Forgiveness and salvation were the Mormon Church’s big-picture promises; the fine print involved no smoking, no imbibing of alcohol, tea or coffee, 10 per cent tithing, the wearing of very strait-laced clothes and passion-killing underwear called ‘garments’ day and night, and polygamy. To Anne, who had lived a restricted life, these matters seemed insignificant. She rapidly became enmeshed in the community of the Church; its strict structure became hers. There were regular social functions, special days of remembrance, fasting once a month, plus a marathon three-hour church service on Sunday (their day of rest). The drab life she had lived as a nanny began to drift into the background. Within a year, however, she bade a sad farewell to the Barneses, who had become like a second family, and relocated to Los Angeles. They promised to keep in touch, and did so.

Representatives from the massive Mormon Temple on Santa Monica Boulevard in Hollywood were there to meet Anne when she arrived. She took a ‘Beverly Hills apartment on the wrong side of the tracks in a street lined with jacarandas’, and become a limousine dispatcher and an insurance underwriter. No job was ever more than the means to an end and an income, however.7 Although living became a purpose in itself, a voice in her head kept nagging her to become a writer. But her frenetic life gave her neither the time nor the opportunity. So when she heard that her stepfather, Bill, was seriously ill she felt called to go home, not just to support her mother, but also because she hoped to silence the voice.

When Anne arrived back in England she initially stayed with Marion and Bill at Watford, but then unexpectedly she found herself able to purchase a property. Her father, Henry Hulme, now Chief of Nuclear Research at the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston, gave her a lump sum of £8,500, along with a monthly allowance of £100. With this money she bought a rundown abode in Darsham, made up of two small farmworkers’ homes ‘knocked together and in a row of five or six tiny terrace houses called Fox Cottages’.8

Ngaio Marsh Her Life in Crime

Ngaio Marsh Her Life in Crime The Search for Anne Perry

The Search for Anne Perry